Bees and Bare Ground

Rethinking Rangeland Management for Native Pollinators

Pollinators play a crucial but mostly overlooked role in Montana rangelands. Livestock and wildlife may dominate the visual landscape, still, the unseen role of insects and spiders, and in this story, the hum of solitary bees quietly maintains much of the ecosystem’s health. The Montana State University Forages Research and Extension Program, our partner Dave Naugle (PhD, University of Montana, and USDA NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife), and former graduate student Gabrielle Blanchette, have released new information on how livestock grazing practices shape the habitats of rangeland pollinators (read the full study online, https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/ieae069). This new paradigm can help lead to rangeland management strategies that recognize the shared interests of people who value open and diverse landscapes and the economic opportunities for rural communities.

Figure 1. Bare ground-nesting habitat in sagebrush steppe rangeland

Photo: Hayes Goosey, MSU Extension

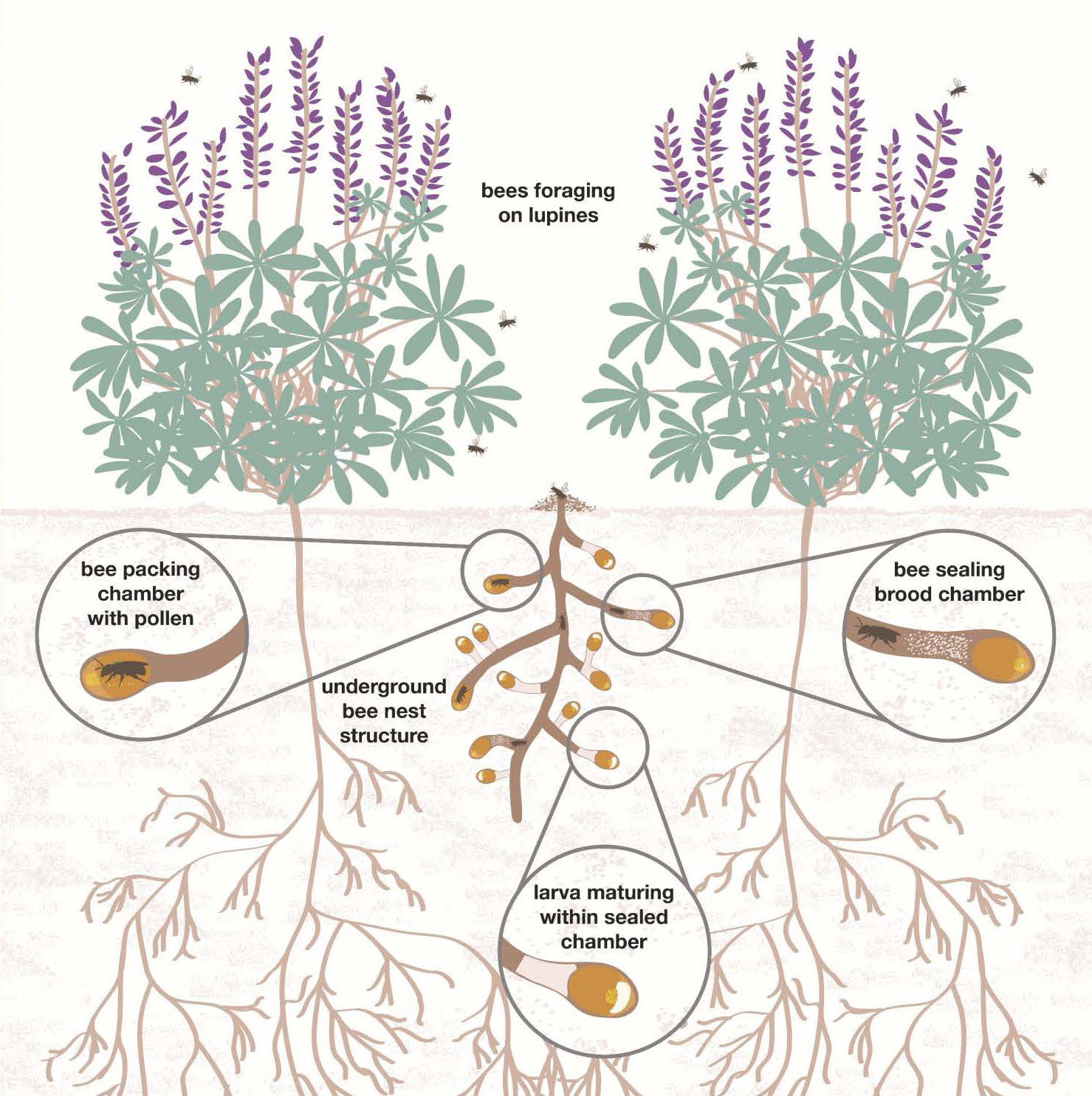

Globally, pollinators matter because they are essential for crop production and maintaining healthy native rangelands. While honeybees, non-native pollinators, often steal the spotlight in crops, ground-nesting bees are unsung heroes of native rangelands. Unlike their hive-dwelling cousins, 70 percent of native bees are solitary, and many rely on open patches of bare soil for nesting (Figures 1 and 2). Solitary ground-nesting bees help pollinate crops like canola and seed alfalfa, but a significant contribution is in the specialized relationships bees have with rangeland wildflowers, many of which are nitrogen-fixing legumes and animal forage. This relationship is essential because, without native pollinators, much of the rangeland plant fauna could not exist. Despite their importance, native ground-nesting pollinators face habitat challenges because of the delicate balance between rangeland vegetation cover and bare ground, especially in working landscapes. Yet, it is here where managed livestock grazing matters.

Figure 2. Eye-level view of multiple nests

Photo: Hayes Goosey, MSU Extension

Animal grazing can impact rangeland plant communities, the structure of plants, and soil health, all of which can combine to positively or negatively impact entire landscapes. The study conducted by MSU and partners explored how grazing intensity affects the availability of bare ground and floral resources, essential components of native pollinator habitats, and the findings reveal a nuanced story where moderate grazing levels create a patchwork of vegetation and exposed soil that benefits native bees. The study also suggests that idling land without grazing allows dense vegetation and thatch to build on the soils, which reduces pollinator nesting sites and reproductive success.

As the research suggests, maintaining small patches (about 15 percent) of bare ground – created naturally by cattle grazing and movement – significantly improved bee nesting opportunities.

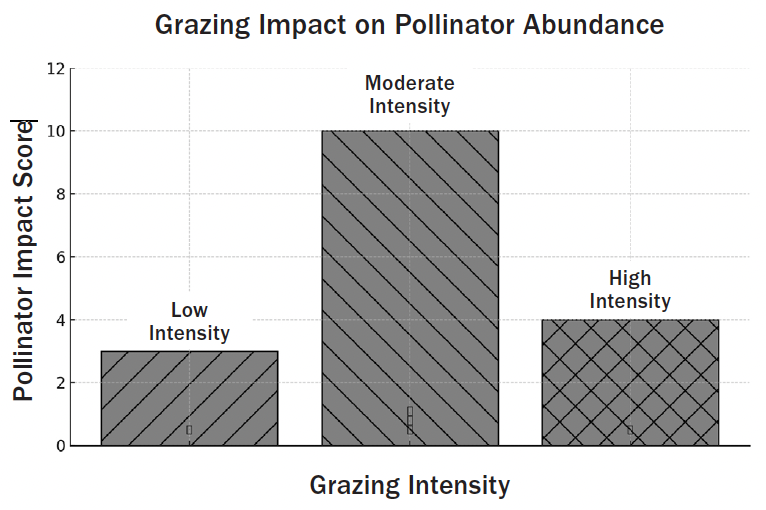

Moderate grazing emerged as the ideal usage in the study (Figure 3) by promoting vegetation heterogeneity – a practice that supports livestock and pollinators. Vegetation heterogeneity refers to the variety of plant heights and the presence of open soil patches, which provide resources for grazing animals (livestock and wildlife) and native, ground-nesting solitary bees. Such landscapes offer abundant forage resources while maintaining the open soil and floral resources many native bees need to thrive.

Figure 3. Research concludes that moderate livestock grazing and site disturbance provide the most nesting sites for Montana’s solitary nesting bee species. This, in turn, produces the highest abundance of pollinators to provide services to rangeland nitrogen-fixing legume plants.

Interestingly, the study also noted variations between pollinator species. Some native bees, namely bumble bees, do best with lower grazing pressure and increased vegetative thatch. Meanwhile, solitary bees prefer the increased nesting sites associated with more bare ground, highlighting the need to maintain a range of habitats to support various pollinators.

Moderate grazing intensity and maintaining vegetation heterogeneity represent a win-win for land managers because livestock grazing supports productive rangelands by fostering plant diversity, which, in turn, supports healthy pollinator populations by enhancing the ecosystem’s resilience via nutrient cycling and plant abundance, specifically flowering legumes.

This research highlights the value of grazing strategies for Montana’s ranchers and land managers. Managing rangelands with pollinators in mind doesn’t require radical change, just a commitment to balance. Rotational grazing can help create the patchwork habitats that solitary bees need. Producers can experiment with adjusting stocking densities and grazing durations to promote the desired vegetation vs. bare ground patterns. Policymakers, state Extension services, and stakeholder groups can help support Montana rangelands by sharing about the interconnected relationship between native pollinators and managed grazing.

Underground schematic of a bee nest

Diagram: Hayes Goosey, MSU Extension

Native pollinators are tiny and usually unseen; however, their role in native landscapes is immense. Understanding how biological systems fit together helps us see how natural livestock grazing patterns benefit pollinator habitats, and vice versa. Moderate grazing isn’t just good for bees – it’s good for the land, the cattle, and the communities that depend on them. With careful stewardship, Montana’s rangelands can continue to hum with life, from the wanderings of cattle to the gentle buzz of native bees, ensuring a thriving future for all.

Hayes Goosey is the MSU Extension Forage Specialist.