Alzheimer's and Related Dementias: Support for Montana Farmers and Ranchers and their Families (Volume 1)

Publication 4641

Reviewers

The authors express appreciation to the following individuals for reviewing one or more articles, for making suggestions for improvement, and for sharing examples of Alzheimer’s behaviors cited in the articles.

- Walt Anseth, Rural Development, Farm & Ranch Loan Manager, Montana Department of Agriculture, Helena

- Renee Brooksbank, Esq, MTGEC Associate Director, Montana Geriatric Education Center, University of Montana, Missoula

- Ilene Casey, MS, Library director, retired

- Pat Coon, Physician, retired; The Montana Alzheimer’s and Dementia Coalition, MD

- Jennifer Erickson, Branch Manager/Relationship Manager, AgWest Farm Credit

- Jesse Fulbright, Liberty County MSU Extension Agent, Chester

- Katie Hatlelid, Former Judith Basin County MSU Extension Agent, Stanford

- Daniel J. Koltz, PhD, Assistant Professor and MSU Extension Gerontology Specialist, Department of Health and Human Development

- Robert E. Lee, Rancher, Lewistown

- Kaleena Miller, Madison/Jefferson County MSU Extension Agent, Whitehall

- Betty Mullette, The Montana Alzheimer’s and Dementia Coalition, Billings

- Ken Nelson, McCone County MSU Extension Agent, retired

- Gary A. Peterson, Caregiver for a friend living with Alzheimer’s, Bozeman

- Renee A. Reijo Pera, PhD, President and Professor, McLaughlin Research Institute for Biomedical Sciences, Great Falls

- Mandie Reed, Wheatland County MSU Extension Agent, Harlowton

- Jan Smith, Montana Alzheimer’s and Related Dementia Coalition

- Jo Ann Warner, Associate Director, Western Extension Risk Management Education Center

- Kristi Williams, Wheatland County MSU Extension Administrative Assistant, Harlowton

- Kimberly Suta Woodring, Toole County MSU Extension Agent, Shelby

- Roubie Younkin, Valley County MSU Extension Family and Consumer Sciences/4-H Agent, Glasgow

The design and printing of this publication is funded in part by a generous contribution from the University of Montana Geriatric Education Center, Western Extension Risk Management Education, AgWest Farm Credit, and AARP Montana.

The design and printing of this publication is funded in part by a generous contribution from the University of Montana Geriatric Education Center, Western Extension Risk Management Education, AgWest Farm Credit, and AARP Montana.

|

|

|

|

|

Authors

- Marsha A. Goetting, PhD, CFP®, Professor and MSU Extension Family Economics Specialist, Department of Agricultural Economics and Economics

- Vicki Schmall, PhD, Emerita Professor and Extension Gerontology Specialist, Oregon State University

- S. Dee Jepsen, PhD, Professor and Extension Agricultural Safety and Health State Leader, The Ohio State University

- Tiffany Hensley-McBain, PhD, Assistant Professor, McLaughlin Research Institute for Biomedical Sciences, Great Falls

- Rebecca Brown, BSN, RN, McLaughlin Research Institute for Biomedical Sciences, Great Falls

Dedication

WHEN I WAS YOUNG, I ENJOYED GOING WITH GRANDPA when he and Grandma came to town to

buy groceries and gas. At the gas station, he would lift me up and sit me down on

the counter saying, “This is my granddaughter, Marsha.” I felt so proud and loved.

Then one weekend when Grandpa and Grandma came to town, he ignored me. Later when

my cousins and I were playing in the wheat field near the farmhouse he yelled at us.

Grandpa had never done that before. What was wrong? I cried because I thought Grandpa

didn’t love me anymore. My mother told me Grandpa was “senile” and it wasn’t his fault

he got upset at us. “Senile” was the term used in the early 1960s. Now the doctor

would likely diagnose Grandpa as having Alzheimer’s.

Fast forward to 2007. My mother started behaving differently. We would find pieces

of paper around the house where she was listing the birth dates of her parents and

siblings. She made her famous deviled eggs for the Anderson family reunion and put

them in the freezer so they would be ready for the big dinner. She had always told

us, “Do not put deviled eggs in the freezer, they will be “uneatable.” She would get

mad and stay in her bedroom all day. She would yell at Dad. These behaviors were not

like my mother at all. By then my sisters and I had read articles about Alzheimer’s,

so the eventual diagnosis was not a surprise.

I dedicate my efforts in the production of Volume 1 of this magazine to my grandpa,

Zephie Ray (1883–1961), who was a dryland wheat and maize farmer in Southwest Kansas,

and to my mother, Sara Lee Ray Anderson (1926–2017), an outstanding 4-H Leader, a

librarian aide who made wonderful displays for the Hugoton (Kansas) Junior High library,

and who was known for her delicious apple pies that were Grand Champion winners at

the Stevens county fair.

Marsha Anderson Goetting

The authors designed Volume 1 of this magazine specifically to reach Montana agricultural producers facing early to middle stages of Alzheimer’s, their families, and family caregivers with information that can make a positive difference in their lives.

Volume 2 will include these tentative topics:

- Creating Safety in the Home

- Wandering and Alzheimer’s: A Safety Concern

- Driving and Alzheimer’s: Concerns and Decisions

- Helping Children Understand Alzheimer’s

- Financial, Health Care and Estate Planning Documents

- Making Long-Term Care Plans

Agricultural Occupations and Alzheimer’s: Potential Causes, Signs, and Early Diagnosis

SINCE DR. ALOIS ALZHEIMER’S DISCOVERY IN 1906, researchers have investigated and theorized about the potential causes of Alzheimer’s. Questions arising from farm and ranch communities include: Is pesticide or solvent use a contributing factor? How about nitrates or fertilizers? Copper? Elevated levels of DDT? Aluminum in the drinking water?

Unfortunately, research has not revealed whether these compounds or environmental

factors contribute to Alzheimer’s and other dementias. This article highlights three

research projects that examined potential causes of Alzheimer’s and related dementias

for individuals involved in agricultural enterprises. Signs of Alzheimer’s and the

importance of early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s are also discussed.

Research on potential causes of Alzheimer’s and related dementias for individuals

involved in agriculture

One study by Dr. Kanitka Arora and colleagues at the University of Iowa found that

people who work long-term in agriculture, fishing, and forestry are 46 percent more

likely to develop dementia than individuals who do not work in these occupations.

“Hearing impairment, depression, and isolation can all be linked to dementia and to

farm work, but it’s possible pesticide exposure is also a culprit,” concluded Professor

Kanika Arora at the University of Iowa College of Public Health. While the Iowa project

is only one study, research is ongoing to determine if persons involved in agriculture

may be more likely to develop dementia.

Dr. Fabio Coelho and researchers from other countries have investigated whether copper

sulfate, widely used in organic agriculture, could be associated with Alzheimer’s.

They concluded when used in excess, copper sulfate can lead to oxidative stress and

harmful effects in people who have a predisposition to copper imbalance. Other studies

have linked chronic exposure to copper sulfate to accelerated cognitive decline and

an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Emily Sturm and other scientists at Colorado State University conducted a project

in which they examined 106 research journal articles using keywords related to agriculture,

occupational exposure, and the brain. They found seven major risk factors:

- Non-specific factors that are associated with agricultural work itself

- Airborne toluene (found in gasoline, paint thinners, paintbrush cleaners, nail polish, glues, inks, and stain removers)

- Pesticide and chemical contact

- Exposure to heavy metals (manganese, arsenic, nickel, zinc, copper)

- Dust exposure

- Working with farm animals

- Nicotine exposure from certain plants such as tobacco

Of these factors, pesticides were studied the most.

The Colorado scientists concluded, “In order to better understand the independent,

cumulative, and multiplicative impact of agricultural risks, better measures and classification

of these occupation subtypes and the duration of time in that profession are needed.

Future studies need to examine the impact of specific agricultural risk factors and

brain health using direct measures of brain structure and function. Since agriculture

employs more workers over the age of 55 than any other industry, literature also needs

to consider the impacts these risk factors may have on brain aging.”

No study has clearly identified the causes of Alzheimer’s disease for individuals involved in agricultural occupations.

Gender and Alzheimer’s disease

Women now make up more than 26 percent of the workforce on Montana’s farms and ranches.

Regardless of the type of operation, spouses are often intimately involved in farm

and ranch businesses. Almost two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women. A

major reason for the higher incidence of Alzheimer’s and related dementias in women

is that women live longer than men. Age is the single most associated risk factor

for dementia.

Women now make up more than 26 percent of the workforce on Montana’s farms and ranches.

Regardless of the type of operation, spouses are often intimately involved in farm

and ranch businesses. Almost two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women. A

major reason for the higher incidence of Alzheimer’s and related dementias in women

is that women live longer than men. Age is the single most associated risk factor

for dementia.

Signs of Alzheimer’s

Although signs of Alzheimer’s disease vary from person to person, the following are

symptoms that may be observed:

- Problems with day-to-day memory: paying home or business bills twice or not paying them at all; forgetting or having

difficulty recalling information such as home address, or the name of a grandchild;

neglecting to deposit checks in the farm or ranch business checking or savings accounts;

forgetting the location of the grazing pasture; losing track of the day or month;

or becoming confused about where they are and wanting to go back to the farm or ranch

home even though they are already there.

- Difficulty making decisions, solving problems, or following steps when completing

a task: having trouble following a recipe; experiencing problems with driving a manual shift

pickup or grain hauling truck, or with using a computer to run the center pivot irrigation

system; or having difficulty remembering how to drive a tractor, combine, or swather.

Other signs include overlooking the need to feed and water livestock or forgetting

to close pasture gates.

- Language issues: being unable to find the right words to offer an opinion on the new farm bill or

to respond to a question about calving, price of grain, fertilizer, pesticide they

are using or whether they will plant wheat or barley this year.

Judging distances: difficulty judging distances when backing up the truck to a trailer for loading

cattle or horses; failure to unload wheat near the auger; driving too close to the

truck in the shed and denting the side door.

Judging distances: difficulty judging distances when backing up the truck to a trailer for loading

cattle or horses; failure to unload wheat near the auger; driving too close to the

truck in the shed and denting the side door.- Mood changes: becoming angry, frustrated, or irritable with a grandson who didn’t brush down his

horse after a ride; being withdrawn or anxious; yelling at the mail delivery person

who didn’t bring a box to the front door and instead left it by the mailbox; or being

unusually sad, which is not the person’s typical mood.

- Visual problems: misinterpreting patterns or reflections, for example, thinking the farm or ranch

pond is an ocean; seeing things that are not there (visual hallucinations) such as

seeing a parent, who died 10 years ago, sitting at the dinner table.

- Changes in behavior: asking repetitive questions, such as “When are we going to combine the south 40?” “When are we going to bale the hay?” “When are we going to town?” or pacing up and down the driveway for no obvious reason.

Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s

Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is critical for a person and their family.

Researchers believe early treatments for Alzheimer’s will be more beneficial. However,

in rural Montana, an early diagnosis can be a challenge because board certified geriatricians

are associated with hospitals in our larger cities.

An early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s has many benefits. It allows a person to be open

with their family and support network about their preferred care during each stage

of the disease. This can give everyone peace of mind, lessen the burden on family

members, and reduce disagreements.

Early diagnosis also enables a person to express their wishes about legal, financial,

and end-of-life decisions; review and update legal documents; discuss finances and

property ownership; and express their health care preferences. Potential safety issues,

such as driving and wandering, can be considered ahead of time. An early diagnosis

is especially important to families who live on farms and ranches where they use complex

machinery and work with large animals.

To learn more about Montanans’ experiences with a diagnosis of dementia, the Montana

Alzheimer’s Coalition (www.mtalzplan.org) facilitated 15 town hall meetings across the state during 2016. Rural farm and ranch

communities were included. Participants at the meetings brought up the issue of trying

to get a diagnosis. They expressed concern, noting that physicians did not seem comfortable

addressing, diagnosing, and/or managing Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia.

A town hall meeting participant said:

“We are blessed with a wonderful medical community, but there is still a gap by medical

providers hesitating at diagnosis and helping with planning and looking at the big

picture [with the patient]. Whether they do not know or don’t want to be the bearer

of bad news, I don’t know.”

In 2022, during a listening session in Bozeman held by the Montana Chapter of the

Alzheimer’s Association, attendees shared similar frustrations. “Nothing has changed,”

one person exclaimed.

The Montana town halls and discussion in Bozeman supported research that finds family

members often wait an average of 18 months for a definitive dementia diagnosis. Fewer

than 50 percent of individuals with dementia and their caregivers reported being told

by their physician about the diagnosis, which is much lower than for most other medical

conditions. Of those informed of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, 84 percent said they were

not provided with education about the disease. They also were not given resources

about caring for someone with dementia. Only seven percent said they received information

about community resources.

The independent nature of farmers and ranchers may contribute to a reluctance to visit a physician. They may be unwilling to ask for help from others because they do not want to appear dependent. They do not want to lose their livelihood, and may fear losing the respect of their neighbors. A farmer or rancher may not want to lose his reputation as a friend who has always been there to help others in need and may not want to be viewed as a needy person. Yet, an early diagnosis enables farmers and ranchers to complete their financial, estate, and health care plans while they have the mental ability to do so.

A farm/ranch perspective

Currently, Alzheimer’s organizations lack resources to address the unique situations

of farmers and ranchers living with Alzheimer’s and their families. People in agricultural

occupations face potential increased hazards and injuries because they live where

they work, as compared to urban workers who often retire or have a medical retirement

after receiving an Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Because of memory loss, farmers and ranchers

may not remember how to correctly use certain equipment. Daily exposure to hazards

and diminished mental ability increases the risk of injury.

Farmers and ranchers also work with large, unpredictable animals that could injure

them. Manure pits with anaerobic bacterial action that breaks down the manure can

increase potentially harmful environmental exposures. Other added dangers on the farm

or ranch include confined spaces such as corral stalls, and vast distances between

home, fields, and pastures. They are often miles from emergency medical care, dementia

experts, and mental health resources.

Alzheimer’s and Other Dementias: NOT a Normal Part of Aging

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE IS THE MOST COMMON FORM of dementia among older adults, accounting for 60–80 percent of cases. The Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention estimates the number of people living with the

disease doubles every five years beyond age 65. The Alzheimer’s Association reported

6.7 million Americans aged 65 and older living with Alzheimer’s in 2023. The number

is expected to increase to 12.7 million by 2050. Alzheimer’s is the seventh leading

cause of death for all adults, both nationally and in Montana.

Montana has more than 22,000 people living with Alzheimer’s. The Alzheimer’s Association

predicts the number will climb to 27,000 by 2025. Unfortunately, no data indicates

how many Montana Alzheimer’s cases are farmers and ranchers.

Alzheimer’s and other dementias are NOT a normal part of aging.

Montana ranks sixth in the nation for its percentage of population over the age of

65. Research shows the risk of developing a neurodegenerative disease increases with

age. Seventy-three percent of individuals with Alzheimer’s are aged 75 or older. For

these reasons, promoting education and expanding community resources about Alzheimer’s

is a priority in Montana.

Montana ranks sixth in the nation for its percentage of population over the age of

65. Research shows the risk of developing a neurodegenerative disease increases with

age. Seventy-three percent of individuals with Alzheimer’s are aged 75 or older. For

these reasons, promoting education and expanding community resources about Alzheimer’s

is a priority in Montana.

Alzheimer’s and other dementias are a major cause of disability and dependency in

older adults. Persons living with Alzheimer’s and their family members experience

significant changes physically, mentally, emotionally, socially, and financially.

The economic cost to families and Montana is significant. There are 17,000 caregivers

in Montana providing 25 million hours of unpaid care with a total value of $474 million.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, Medicaid costs for people with Alzheimer’s

in Montana during 2020 were $166 million. The Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease

projects the cumulative total cost of Alzheimer’s disease in Montana from 2017–2030

will be $2.89 billion. The Genworth Cost of Care Survey indicated that in 2023, the

average cost per day for a private room in a long-term care facility in Montana was

$8,060 per month ($96,720 annually).

Discovery of Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer. In 1906, Alzheimer noticed changes in the brain tissue of a woman who died of an unusual mental illness. Her symptoms included memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behavior. After she died, Alzheimer examined her brain and found abnormal clumps (now called amyloid plaques) and bundles of tangled fibers (now called neurofibrillary or tau tangles). What is still not fully understood is the cause of these plaques and tangles.

Source: Melanie Williams, Program Director, Alzheimer’s Association, Montana

Source: Melanie Williams, Program Director, Alzheimer’s Association, Montana

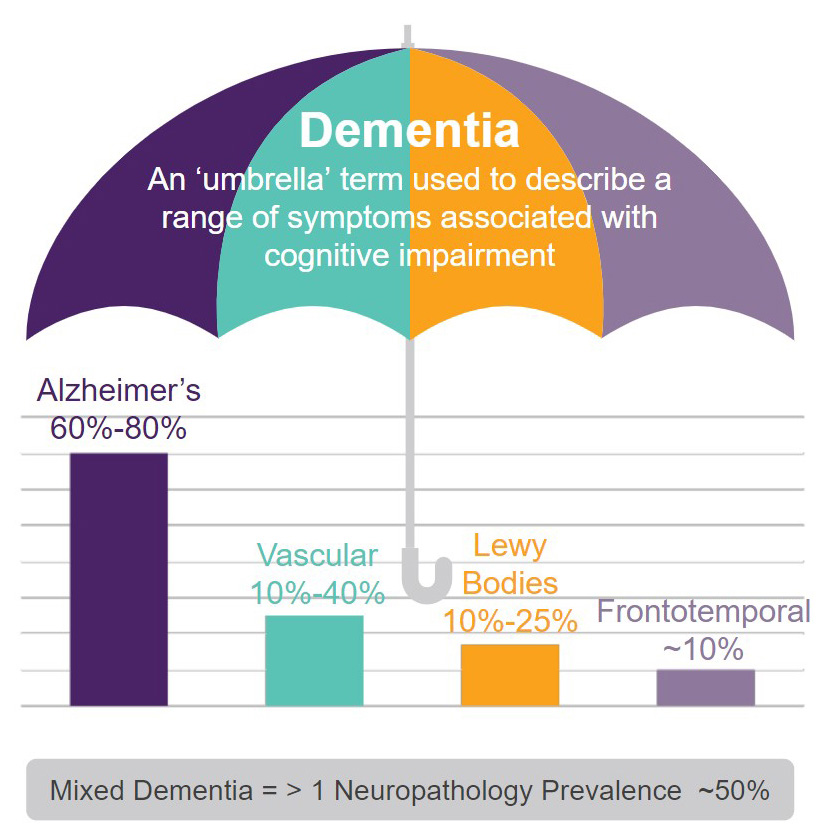

Types of Dementia

All forms of dementia have a loss of connections between nerve cells (neurons) in

the brain. Neurons send messages between various parts of the brain, and from the

brain to muscles and organs in the body. While all dementias have symptoms similar

to Alzheimer’s, symptoms vary from person to person depending on other health conditions

and cognitive function before dementia.

Alzheimer’s typically begins with short-term memory loss, but this is not true of

all types of dementia. With Lewy Body dementia, a person is more likely to experience

hallucinations and act out during sleep. A person with Frontotemporal dementia often

develops behavior and personality changes early in the disease.

Vascular dementia is caused by decreased blood flow to the brain resulting from conditions

that damage blood vessels. Blood circulation is reduced, depriving the brain of oxygen

and nutrients. Heart disease and stroke are risk factors for vascular dementia. Diabetes,

high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking increase the risk.

Other medical conditions — including severe or repeated brain injuries — can result

in dementia.

Researchers have recently found many people have “mixed dementia,” meaning they experience

two or more dementias simultaneously. Having both Vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s

disease is common. Mixed dementia is most prevalent in the brains of people aged 80

and older.

Unfortunately, ALL dementias are progressive over time, and are currently NOT reversible.

Although there are ongoing research trials with studies of treatments and therapies, currently there is NO treatment to cure any form of dementia. Therapies and medications are available to help protect the brain and manage symptoms such as anxiety and behavior changes.

Sources of Accurate Information About Alzheimer's and Related Dementias

The Alzheimer’s Association was formed in 1980. The organization supports accelerating global research, risk

reduction, early detection, and maximizing quality care and support. Anyone concerned

about memory loss can access the Alzheimer’s Association website to learn more. alz.org

Montana also has a state Alzheimer’s Association with staff available to help families

with information. They have educational programs that are virtual and in-person. alz.org/montana

AARP offers a variety of caregiver information. aarp.org/caregiving

Montana Senior and Long-Term Care Division has a website with Alzheimer’s information. The Legal Developer program can provide

one-on-one legal help. dphhs.mt.gov/sltc or 1-800-332-2272.

Montana Alzheimer’s and Related Dementia Coalition is a state-wide partnership consisting of several national, state, and local partners

interested in improving care and support to Montanans with Alzheimer’s disease and

other related dementias, their families, and caregivers. mtalzplan.org

Montana State University Extension has educational resources about Alzheimer’s. There are Montana fact sheets about

legal and financial alternatives in a “Concerned about Memory Loss” packet, and a

worksheet “My Life, My Values.” montana.edu/extension/alzheimers

Alzheimer’s Foundation of America offers support, services, and education to individuals, families, and caregivers

affected by Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The Foundation also funds research

for better treatment and a cure. alzfdn.org

The National Institute on Aging within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) offers families information about Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The

institute also has many resources for caregivers. .nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-and-dementia

Progression of Alzheimer's

ALZHEIMER’S TYPICALLY PROGRESSES SLOWLY IN three general stages: early, middle, and

late. Physicians often refer to the stages as mild, moderate, and severe. Although

Alzheimer’s gets worse over time, the rate of progression varies widely among individuals.

A person with Alzheimer’s lives an average of four to eight years after diagnosis

but could live as long as 15 to 20 years, depending on other factors.

Preclinical Alzheimer’s

Changes in the brain because of Alzheimer’s begin years before any signs appear. Physicians

call this period, which often lasts for years, preclinical Alzheimer’s. There are

NO outward symptoms. This “phase” is not noticeable to the person or others.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

People with MCI have problems with memory and thinking that are more prominent than

in other adults their age. The potential for MCI increases with age. An assessment

by a physician is important to determine if memory issues are due to something treatable.

According to the National Institutes of Health, researchers found more people with

MCI than those without it go on to develop Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias.

An estimated 10 to 20 percent of people 65 and older with MCI develop dementia over

a one-year period. However, not everyone who has MCI develops dementia. In many cases,

the symptoms of MCI may stay the same or even improve.

According to the Mayo Clinic, people with MCI have mild changes in their memory and

thinking ability. These changes are not significant enough to affect daily life, work,

or relationships with family, friends, and colleagues. People with MCI may have memory

lapses for information usually easily remembered, such as conversations, recent events,

and appointments. Making sound decisions often becomes more difficult. A person with

MCI will often forget a step in a series and may stop doing an activity because they

do not know what to do next.

People with MCI may also have difficulty judging the amount of time needed to correctly

sequence and complete a task’s steps. As an example, think about the steps necessary

for a farmer or rancher to pay a business bill.

- Get the mail out of the rural mailbox.

- Sort through the mail to find the bills.

- Open the envelope and find the amount due on the bill.

- Find the checkbook and write a check for the correct amount.

- Find an envelope.

- Slip the bill and check in the envelope for mailing.

- Seal the envelope.

- Find a stamp with the correct postage amount.

- Put the stamp on the right side of the envelope.

- Place the envelope in the mailbox.

- Put up the mailbox flag so the postal carrier knows to pick it up.

Notably, because “safety on farms and ranches is so important, if you miss one safety step, it could mean a difference of life or death,” says Arlene Hahn, client and program manager with the Alzheimer Society of Alberta and Northwest Territories in Canada.

Early-stage Alzheimer’s (mild)

Physicians often diagnose Alzheimer’s in the early stage, when it becomes clear to

family members that a person is having significant difficulty with memory and thinking

that affects daily functioning.

According to the Mayo Clinic, during the early stage of Alzheimer’s, people may experience:

Memory loss of recent events. People may have difficulty remembering newly learned information and ask the same

question repeatedly.

- Grandma does not remember how to use the new air fryer she received on her birthday even though her daughter has described the steps many times.

- Grandpa does not remember his new truck has an automatic shift, not a manual, although his grandson has reminded him every time.

- Mom does not remember how to use the remote for her new television. She wants to use the same steps as she did with her old remote.

Difficulty with problem solving, complex tasks, and sound judgments. Planning a family event or balancing a checkbook may become overwhelming. A person

may experience lapses in judgment, for example, when making financial decisions.

- Grandma wrote a $100 check to every charity that sent a request in the mail. She did not realize she had already donated over $3,000 that month.

- Grandpa went to the bank to get $500 in cash but instead withdrew $5,000 and wondered why the bank teller asked, “Are you sure you want all this cash?"

Changes in personality. A person may become subdued or withdrawn, especially in challenging social situations,

or show uncharacteristic irritability or anger. Reduced motivation to complete tasks

is common.

- Mom did not want to get out of the truck at a neighbor’s ranch home because she appeared frightened by the three barking dogs that raced to greet them. During past visits she was comfortable with the dogs, petting and talking to them.

- Dad became agitated and angry at his adult son for stopping in the middle of the county road to visit with a neighbor.

- Grandpa was angry at his granddaughter because he believed she was just “goofing off”

when she attended a two-day agricultural trade show.

Difficulty organizing and expressing thoughts. Finding the right words to describe objects or clearly expressing ideas becomes increasingly challenging.

- An uncle wants the keys to the truck but calls them “Those things you use to start the truck.”

- An aunt searches for her knitting needles so she can knit a dishcloth. When she sees

sharpened pencils, she tells her niece, “The search is off, I have finally found my

knitting doodads.”

Getting lost or misplacing belongings. Someone may have increased trouble getting around, even in familiar places, and may misplace things, including valuable items.

- A grandmother in eastern Montana decided not to wait for her son to go with her when she was returning to the ranch from town, a place she has lived for 60 years. She became disoriented and took three hours to get home — the trip usually only took 45 minutes.

- A grandfather accused his oldest grandchild of stealing money out of his billfold, not remembering he had spent the $50 in town.

- A mother accused a good friend of taking her favorite piece of jewelry.

Middle-stage Alzheimer’s (moderate)

During the middle stage of Alzheimer’s, a person becomes more confused and forgetful.

More help is needed with daily activities and personal care. Individuals lose track

of where they are, the day of the week, and the season.

According to the Mayo Clinic during the middle stage, a person may:

Show intensified confusion. This makes it unsafe to leave a person at home alone.

- A farmer or rancher may confuse family members or close friends with one another or mistake strangers for family.

- A dad called his adult grandson by his father’s name, possibly because the grandson looks very much like his father.

- A grandma turned the microwave on for 15 minutes to warm up a dinner roll and became

aggravated at her granddaughter when she rushed over to turn it off.

Display increasingly poor judgment. Sometimes a person may take an inappropriate action before others realize what has happened.

- A grandfather climbed into the cab of the combine, started it, and drove down a path to the highway before his son and granddaughter could stop him. They were so surprised they stood and watched. Finally, the granddaughter drove the truck alongside the combine so her dad could signal to Grandpa to stop.

- A father demanded his son start baling hay right after lunch even though rain had

fallen all morning and continued into the lunch hour.

Experience greater memory loss. People may forget details about their personal history, such as their address or phone number or where they buy groceries. They may repeat favorite stories or make up stories to fill gaps in memory.

-

- A grandmother who formerly embraced modern technology got angry when her grandson tried to show her again how to use the new cell phone. She did not remember the grandson teaching her last month. Because memory loss is significant in Alzheimer’s, the grandson’s directions could not be recorded in her brain for later retrieval.

- A family in south central Montana had the same challenge trying to get their grandmother to use the television they gave her for her birthday. She couldn’t remember how to turn it on and said she didn’t like to watch television anymore.

- A farmer had trouble differentiating between the barn and shop, where he was to meet his son to help weld a disc.

- A rancher was constantly asking the whereabouts of his son and grandson even though he had been told many times they were attending an economic conference.

- One rancher got lost when checking the cows. He could not remember his way home and

ended up in a town 60 miles away.

Need help with daily activities. A person may need help choosing proper clothing for the weather or an occasion. The person may need help with bathing, grooming, using the bathroom, and other self-care activities.

- A rancher no longer attends agricultural conventions because he has lost his bladder and bowel control.

- A caregiver shared, “My husband cannot find the bathroom in the home we have lived in for 50 years.”

- Another caregiver said she added Velcro to her husband’s shirts because he could no

longer button them.

Undergo significant changes in personality and behavior. People sometimes develop agitation, aggressiveness, and unfounded suspicions. For example, a person may become convinced that friends, family, or professional caregivers are stealing from them.

- A grandmother accused her granddaughter of stealing her ruby necklace.

- A farmer loaded a shotgun and slept on the sofa in the living room because he was convinced people were “out there” who were going to steal his farm.

See or hear things that are not there. A person may become convinced they see or hear things that make sense to them.

- A farmer thought Flathead Lake was the Pacific Ocean and wanted to go fishing in it for Pacific Blue Marlin.

- A rancher was convinced a cattle rustler was hiding in the barn with a gun.

Become restless or agitated. Towards late afternoon or evening as daylight begins to fade, a person may get restless, anxious, agitated, angry, or more confused. Physicians refer to this as “sundowning.”

- A farmer in southwestern Montana became restless and walked inside the home, making a circle from the living room to the bedroom, five or six times every night.

- A wife shared, “Every night around sundown my husband would get anxious and look out the window. Then he would sit down and two minutes later get up and look out the window again. This usually went on for an hour. He was very agitated when doing this.”

Display outbursts of aggressive physical behaviors. A person with Alzheimer’s may strike out with hands or feet, which is an unusual

behavior for the person.

Display outbursts of aggressive physical behaviors. A person with Alzheimer’s may strike out with hands or feet, which is an unusual

behavior for the person.

- A wife was physically violent to her husband of 70 years in the middle of the night because she saw him as a stranger in her bed and home. The bruises were obvious to their daughter when she visited, but both parents said he had a fall.

- A husband tried to hit his wife with his hand, but she avoided his swing and quickly left the room. Several minutes later she came back. Her husband said, “Hi honey, where have you been?” Then he hugged her and told her he missed her. He did not remember his anger nor trying to hit his wife.

Late-stage Alzheimer’s (severe)

During the late stage of Alzheimer’s, a person’s mental function, movement, and physical

capabilities continue to decline. According to the Mayo Clinic, people in this stage

generally:

Lose the ability to communicate coherently. Individuals may no longer be able to converse or speak in ways that make sense, although they may occasionally say understandable words or phrases. Their talking may sound like “gibberish.”

- A farmer in central Montana walked in circles from the kitchen to the living room. He made sounds and gestures to the person he saw in a full-length mirror, not realizing the person he saw was himself.

- A rancher who was visited by friends “grunted” at every question asked by them. This

was his only method of communication.

Require daily help with personal care. Individuals may become agitated when the family caregiver wants them to take a bath, shower or wash their hair.

- A formerly independent rancher needed total help with eating, dressing, using the bathroom, and all other daily self-care tasks. During meals, his wife needed to spoon-feed him.

- A mother cried and screamed when her daughter tried to give her a shower.

Experience a decline in physical abilities. A person may not be able to walk without help and may be incapable of sitting or holding up their head without support. Their muscles may become rigid and reflexes abnormal. Eventually, a person may lose the ability to swallow and control bladder and bowel functions.

- A woman in northeast Montana had to give up Sunday drives with her husband because he could no longer get in and out of the SUV or pickup truck.

- Another woman bought a hospital bed so she could better care for her husband who could

no longer get up, talk, or control his bladder and bowel functions.

Difficult decisions

As Alzheimer’s progresses, a person may need more help than can be provided at home.

Also, their safety may be an increasing concern.

- A husband may fall on the way to the barn but can no longer stand back up by himself. The wife may not realize he left the house.

- A wife may not be aware her husband left the house and is wandering in the corral with the heifers.

- A grandmother may fall in the kitchen, but her husband with Alzheimer’s does not know how to help her up, nor does he know how to call 911.

The farmer or rancher living with Alzheimer’s may want to stay in their home. The

spouse may want the same. Adult children may need to intervene and persuade a parent

to accept the reality that the parent with Alzheimer’s now needs more help than the

spouse and other family members can provide in the home.

Finding a memory care unit or a nursing home, although it is hours away, may become

imperative to meet the care and safety needs of the person with Alzheimer’s and preserve

the health of the spousal caregiver.

Alzheimer's and Caregiver Wellness

A DIAGNOSIS OF ALZHEIMER’S in a farm or ranch family member often means significant changes in the life of the

family caregiver, as well as in the life of the person who has Alzheimer’s. The world

may feel as though it has been turned upside down. A caregiver may experience feelings

of loss and grief. As Alzheimer’s progresses, the disease gradually changes the person

a caregiver has always known. Roles change dramatically, often beginning early in

the disease. Eventually, the person will need around-the-clock care and supervision.

Although caregiving can be rewarding, fulfilling, and meaningful, the responsibility

also can be overwhelming, challenging, and detrimental to physical and mental health.

It is even more intense when juggling caregiving with a job and/or managing other

obligations. Caregiving also involves heart-wrenching decisions, such as ensuring

the person no longer drives, bringing in outside help and possibly moving the person

with Alzheimer’s from their home.

Providing care to a person with Alzheimer’s can be intense and stressful and often

spans a longer time (4 years or more) than caregiving for someone with other medical

conditions. Levels of depression and anxiety tend to be higher in family caregivers

of someone with dementia than in other family caregivers.

In general, people who have Alzheimer’s or other dementias require more supervision.

They are less likely (due to inability) to express appreciation and gratitude for

the help given. Dementia-related behaviors — such as wandering, agitation, aggression,

inappropriate behavior in public, personality and behavior changes, and not recognizing

family members — can be particularly disturbing and challenging.

Stress also tends to be greater if there is little choice in becoming a caregiver

or if your relationship with the person who needs care has been difficult. Caregiving

can take a serious toll on health and well-being. Too often caregivers neglect their

own health, medical care, and emotional needs. This is detrimental to the caregiver

and to the person depending on care.

Take care of yourself

Self-care is vital to maintaining physical, mental, and emotional health. Self-care

is also critical to providing the best care to a person with Alzheimer’s. As an example,

before a plane takes off, one of the flight attendants announces, “If oxygen masks descend, put your oxygen mask on first before helping anyone else.” Only when we first put on our oxygen mask, can we safely help someone else.

- Feeling overwhelmed

- Becoming socially isolated

- Sleeping too little or too much

- Becoming easily irritated or angry

- Feeling tired much of the time

- Gaining or losing weight

- Losing interest in activities previously enjoyed

- Feeling sad

- Experiencing depression

- Using alcohol or drugs, including prescription medications, excessively

Know the early warning signs of stress. Then, take action. Focusing on personal needs

is not selfish. For example, if the person with Alzheimer’s is asking for the tenth

time, “Is today Tuesday?” and without thinking, you yell, “I have told you 10 times already today is Tuesday!”, excuse yourself and leave the room. Walk outside or somewhere private while taking

calming breaths.

Focusing on the need to remove yourself for a brief period to regroup is not selfish.

Find a calendar to show the person the day of the week. Circle the day so the next

time you are asked, “Is today Tuesday?”, you can show the calendar. Or use a cell

phone to show the day of the week. The person with Alzheimer’s isn’t asking the question

just to be cantankerous… there is no memory that the question has been asked before.

Caregiver exhaustion and burnout, illness, or death often precipitate the placement

of a person with Alzheimer’s in a long-term care facility. As a caregiver, do not

place your needs “on the back burner.” Caring for yourself is the most important —

and often the most forgotten — thing to do for yourself.

If you tend to ignore personal needs, ask yourself: What is keeping me from taking

care of myself? Am I being a martyr? Do I think I am the only one who can care for

my spouse or family member? Do I feel guilty because early on I didn’t realize my

family member had Alzheimer’s? If the answer is yes, begin to accept you have needs

as well. Then, move forward one small step at a time.

Not everyone has the skills to be a caregiver, and that is okay. Crucial factors to

consider before assuming a caregiving role include your health, abilities, comfort

level with caregiving, other responsibilities, and the quality of your relationship

with the person who needs care.

Mastering caregiver wellness

There are actions you can take to increase your wellness and self-care as a caregiver.

LEARN ABOUT ALZHEIMER’S. By learning more about Alzheimer’s you will become more confident, develop needed

caregiving skills, and make better decisions. Become aware of common changes as the

disease progresses. Learn about the care needs of your family member now and in the

future. As Alzheimer’s advances, the person is less and less able to remember, use

good judgment, control their behavior, and perform simple tasks like dressing oneself.

The person’s abilities, personality, behaviors, and communication skills will deteriorate.

The disease also “steals” from the person the ability to make changes. The caregiver

and others must be the ones to change their behavior and communication methods.

A key to providing care and support is seeing the world through the eyes of the person

with Alzheimer’s. The person will see the world differently than you do. What they

see is very real to them. Step into the person’s world. Don’t try to force the person

to fit within your reality. Build on the person’s changing abilities, interests, and

strengths. Create an environment in which the person feels respected, cared for, and

has a sense of belonging.

SET REALISTIC EXPECTATIONS. Setting realistic expectations for yourself and for the person to whom you provide

care is essential. As Alzheimer’s progresses, you will need to re-adjust expectations.

Recognize what you can control and what is out of your control.

Saying “no” to requests from others that require more work, or that you can no longer

do is healthy. As one family caregiver shared, “I finally told my family that I no

longer have the energy and time to host holidays at our ranch home.” Another family

caregiver told her adult children, “While I would like to continue our tradition of

Sunday dinners at the farm, I simply can’t do it anymore. Can one of you please take

over?”

Recognize there may come a time when your family member needs care beyond what you

alone can provide. Consider options and make plans for care in advance of need. If

you should become ill, need surgery, or if an emergency arises requiring your presence,

who will take care of the person with Alzheimer’s?

HOLD A FAMILY MEETING. A family meeting can be a great tool for getting family members engaged and on the

same page about care plans. It can also help with obtaining support, delegating tasks,

and reducing family conflict. Holding a meeting at a place where everyone will feel

comfortable is important. Perhaps holding the meeting at the farm or ranch home may

be too emotional. The earlier discussions begin and decisions are made about caring

for the person with Alzheimer’s, the better it will be for everyone.

ASK FOR AND ACCEPT HELP. Some caregivers find asking for and accepting help difficult. Yet, it is so important

to ASK and ACCEPT. Do not try to go it alone and do everything yourself. Reaching

out for help is a sign of personal strength, not weakness. Look for sources of help

inside and outside your family. Help can also come from community resources and professionals.

“Ask for help earlier rather than later” is direct advice from other caregivers. Don’t

wait until you are overwhelmed, exhausted, burned out, or your own health deteriorates.

Most people are happy to help if they know what to do. Consider making a list of how

others can help. Say “yes” to offers of assistance. When someone asks, what can I

do to help, tell them or show them your list and ask, “Which of the tasks would you

be able to do?”

The way we ask for help can have an impact. Do not make requests that sound guilt-producing,

manipulative, or demanding. Be specific when asking for help: I would like someone

to buy groceries; I need someone to take the ranch truck for an oil change; I can’t

start the swather; would you check it out? These are called “I” statements. Avoid

using “You” statements: You should be more helpful. You never help me with Dad. You

have a responsibility to also help.

Some family members and friends may feel uncomfortable with caregiving tasks. Yet,

they may be very willing to do tasks unrelated to caregiving such as mowing and cleaning

the yard, branding calves, picking up groceries, stacking hay bales, running an errand,

spending time visiting with your family member, or preparing a meal. If someone is

uncomfortable doing what you need, respect that person’s feelings and ask another

person to help.

Personal attitudes and beliefs can be barriers to asking for help. Do you have any

attitudes that keep you from asking for help? Some attitudes expressed by caregivers

include:

- This is my responsibility and mine alone. This viewpoint places a caregiver at greater risk for illness.

- I shouldn’t have to ask for help. People should know I need help. That’s unrealistic to expect. Family and friends are not mind readers.

- If I don’t do it, no one else will. Not true, others are willing to help if asked. They may not know help is needed.

- No one can care for my loved one as well as I can.

- My loved one doesn’t want anyone else to help. He only wants me.

- I would feel selfish asking someone to take care of my spouse while I go out with friends.

- I made a promise to myself and my loved one and I must keep it.

These attitudes can lead to a caregiver feeling more isolated, frustrated, and depressed.

If it’s difficult to ask for help, can someone be hired to get some things done?

TAKE BREAKS FROM CAREGIVING. Too often caregivers feel guilty or selfish for taking breaks. However, regular

breaks are as important to health as meals and exercise. Taking breaks is not selfish.

Breaks are critical for recharging and avoiding burnout. Self-compassion is essential.

Self-compassion means:

- Give yourself credit for the tough work of caregiving

- Limit negative self-talk

- Plan time for yourself

Scheduling time every day for yourself to do something you enjoy is healthy. Remember,

there is no reason to feel guilty.

Family and close friends may be able to spend time with your family member so you

can get breaks. In some communities, an adult day program and/or in-home respite care

is available. Some care facilities also offer adult day programs and short stays so

family caregivers can take a short break or a needed vacation. Find out if any facilities

in your community provide this service.

MAINTAIN MEANINGFUL RELATIONSHIPS. Caregivers who take time to meet their needs for companionship and recreation feel

less trapped and isolated. Thus, they are better able to care for their family member.

Connecting with people you can easily talk to about your feelings and experience is

important. They can be a source of comfort and emotional support.

JOIN A SUPPORT GROUP. Consider joining an online or a local in-person caregiver support group through

the Alzheimer’s Association, alz.org/help-support/community/support-groups. Family caregiver support groups are also available through some hospitals and senior

service organizations, such as a senior center. Support groups can provide a safe

place to:

- Share feelings, experiences, and concerns

- Receive support

- Talk with other caregivers in similar situations

- Learn strategies for coping with challenging situations and behaviors

You may feel you are not alone because of the common experiences. Members of a support

group may validate your emotions and how you managed a difficult situation. Sharing

with others also reduces feelings of isolation and guilt. Some caregivers report their

support group has become their lifeline.

MAKE AND KEEP MEDICAL APPOINTMENTS. Family caregivers often postpone or do not make medical appointments for themselves.

Make sure to continue with regular checkups and screenings. Let your doctor know you

are a caregiver and share any concerns and symptoms. And, if you experience depression

or other overwhelming emotions, seek treatment. Montana State University Extension

provides a MontGuide (fact sheet) explaining different types of mental health providers

and how they can help, store.msuextension.org/Products/Understanding-and-Finding-Mental-Health-Providers__MT201905HR.aspx.

EXPLORE COMMUNITY RESOURCES. Accessing local resources is one way to ease caregiver stress. Housekeeping, in-home

care, meal delivery, transportation, and other caregiving services may be available.

Hiring in-home care help may reduce your burden and enable you to continue providing

care. Adult day care programs or respite services in a care facility can give you

a break from caregiving for a few hours, days, or even weeks while your family member

receives needed care. Below are resources that may be available in your community:

- Aging & Disability Resource Center (ADRC) is a good place to start for information, referral, and assistance. Currently, there are nine Montana Area Agencies on Aging named as ADRCs. An ADRC will have information about classes, support groups, and community services for family caregivers. montana.my-adrc.org

- Alzheimer’s Association offers resource information, educational programs about Alzheimer’s disease, and support groups for family caregivers. alz.org/help-support/community/support-groups

- Alzheimer’s Foundation of America has resources for caregivers who are caring for individuals with Alzheimer’s or other dementias. alzfdn.org

- Eldercare Locator can help identify local community services. eldercare.acl.gov

Plan for care

The time may come when you are no longer able to provide the needed care. Consider

long-term care options early — for example, in-home help and long-term care facilities.

Long-term care involves services provided within the home as well as in care facilities.

As Alzheimer’s progresses and needs change, re-evaluate plans. If a move to a care

facility such as memory care is needed, your role as a caregiver is still important.

Whether you provide around-the-clock direct care or coordinate the care by others,

you are still the caregiver.

The National Institute on Aging offers free worksheets to help caregivers coordinate and keep track of caregiving responsibilities and needs. These worksheets include:

- Coordinating caregiving responsibilities

- Questions to ask before hiring a care provider

- Home safety checklist

- Managing medications and supplements

- Questions to consider before moving an older adult into your home

- Important documents and paperwork

The worksheets are available at: nia.nih.gov/health/caregiver-worksheets. You can also sign up for e-alerts about caregiving tips and resources.

Reminder

To be the best caregiver possible, attending to your physical and mental health and

well-being is critical. Find what works for you. Remember, taking care of yourself

is important to continue to provide the best care for a member of your family who

has Alzheimer’s.

Communicating about an Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

WHETHER YOU HAVE BEEN DIAGNOSED WITH Alzheimer’s or someone close to you, a consideration may be when and how to share

the diagnosis with family members, close friends, and others.

- A family wanted to keep the diagnosis quiet because the husband held a position in public office.

- A wife stopped going to local meetings because she didn’t want to respond to questions about her husband’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

- A family stopped taking Grandma to social gatherings because her unusual behaviors were embarrassing.

Take the time to process the diagnosis and what it means. Coming to terms with the

diagnosis in oneself or in a family member takes time. You may struggle for a while

or go through a period of denial. You may try to convince yourself the physician is

wrong.

Take the time to process the diagnosis and what it means. Coming to terms with the

diagnosis in oneself or in a family member takes time. You may struggle for a while

or go through a period of denial. You may try to convince yourself the physician is

wrong.

It’s important to feel comfortable with a decision to tell others. Start by telling

the people you feel closest to. They are the ones who will encourage and support you.

The earlier you tell family and friends, the sooner they can begin giving support.

If you are the caregiver, talk with the person who has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s,

and respect their privacy. If possible, actively involve them in making decisions

early on about who, how, and when to share their diagnosis. There is no right or best

way to share the information.

You may choose to communicate face-to-face, during a phone call, by writing a letter,

sending an email, or even texting the news with a cell phone. All five methods may

be used, depending on who you are notifying.

Telling family and friends about an Alzheimer’s diagnosis can feel like an overwhelming

task. However, sharing may help with acceptance of the diagnosis. You may also find

that family and friends have noticed changes in your family member who has Alzheimer’s.

In addition to the family physician, other health care professionals — such as the

dentist, optometrist, or dermatologist — also need to know about the diagnosis to

provide the best service.

Communication tips

Consider these tips when talking to family and close friends about the diagnosis of

Alzheimer’s:

BE HONEST. Explain the symptoms the person has shown and how the physician made the diagnosis.

Talking openly about Alzheimer’s with those you trust is a powerful way to educate

others about the disease and to engage their support.

BE PREPARED FOR DIFFERING REACTIONS. Reactions may vary among family and friends upon hearing the diagnosis. Most will

be empathetic and supportive. Others may not know how to respond and remain silent.

Some may not want to accept the news and are in denial. Still others may be overwhelmed.

They may feel uncomfortable and pull back or withdraw from contact for a while. Some

may make comments that reflect misconceptions about Alzheimer’s. Responses may include,

“But you seem to be fine” or “She is too young to have dementia” or “He is too educated

to have Alzheimer’s.” Anticipate how to respond to potential diverse reactions from

others.

EDUCATE ABOUT ALZHEIMER’S. The more people learn about Alzheimer’s, the more likely they are to be comfortable

around the person. Two important points to share are: Alzheimer’s is a disease that

causes brain cells to degenerate and die; and Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease,

meaning symptoms will increase over time. When people have a better understanding

of Alzheimer’s, they are better equipped to provide support to an individual with

the disease.

SHARE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES. Share copies of this magazine and other information when you share the diagnosis.

Consider sharing printed information from the Alzheimer’s Association and referring

individuals to the organization’s website (alz.org). Also, share with them that the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America (alzfdn.org) is a reliable information source.

EMPHASIZE THE POSITIVE. Once the diagnosis is shared, in addition to talking about the person’s limitations,

let people know what activities the person still enjoys and can do. For example, Dad

can help hold the calves during branding.

ENCOURAGE INTERACTION. Family and friends may wonder what changes, if any, they should make in their contacts

with the person. Explain that social interaction and being engaged in familiar and

enjoyed activities can support the person’s remaining abilities and skills. Share

these guidelines for positive communication and interactions:

- Engage in activities that are familiar

- Approach slowly and from the front

- Make eye contact when speaking

- Speak clearly and slowly, using short sentences

- Give time for the person to respond

- Talk directly to the person

- Make sure body language is positive

- Be aware of your tone of voice and facial expressions

- Have patience when the person has difficulty finding words

- Don’t engage in complex or fast-paced conversation

- Avoid correcting if the person uses the wrong word or forgets something

- Don’t ask direct questions about whether the person remembers something

- Avoid saying, “Don’t you remember…?” and “I already told you…”

|HELP CHILDREN UNDERSTAND. When a family member has Alzheimer’s, it affects everyone in the family, including

children and grandchildren. They may feel confused, embarrassed, or afraid and have

questions. More information will be included in Volume 2 of

this magazine.

When in public places

Caregivers often find it helpful to carry a small Alzheimer’s “companion card.” They

can discreetly hand the card to another person letting them know the person with them

has Alzheimer’s and could make an inappropriate comment, display unusual behavior,

or take longer to make a decision.

The card allows you to quietly let someone know about your family member. For example,

the card may be handed to a server at a restaurant, a store clerk when shopping, a

receptionist or professional at an appointment, and airline staff.

Informational cards can be ordered online from the Alzheimer’s store (alzstore.com). You can make and print custom cards. For example, caregivers have made their own

cards with the following messages:

- My husband has Alzheimer’s. He might say and do things that are not correct. Thank you for your understanding.

- The woman I’m with has Alzheimer’s. Please be patient with her. Thank you.

- The person with me has problems with memory. Thank you for your patience.

- My mother has an illness which causes memory loss and confusion. Please excuse any unusual behavior.

Keep communication ongoing

Some friends and acquaintances may drift away, perhaps for just a brief time. They

may be uncomfortable with the Alzheimer’s diagnosis. They may not have experienced

any family member with the disease and believe they can’t relate with the person.

Understanding and acceptance of the diagnosis by others can

help ensure they will continue to interact with your family member.

Continuing to communicate with family and friends, especially those who are a part

of the life of the person with Alzheimer’s, is crucial. As Alzheimer’s progresses,

everyone needs to be informed of changes in the person’s functioning and abilities,

including communication. For example, when a farmer or rancher no longer knows a person

who visits, it’s important for a visitor to understand it’s Alzheimer’s and not take

it personally.

Hope for the Future: Treatments or a Cure for Alzheimer’s?

Authors: Tiffany Hensley-McBain, PhD and Rebecca Brown, BSN, RN

MOST CURRENTLY APPROVED THERAPIES FOR Alzheimer’s disease manage the symptoms. These include cholinesterase inhibitors

for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) for moderate

and severe Alzheimer’s disease. The goal of these therapies is to decrease cognitive

and behavioral symptoms; however, they do not change or cure the disease.

In 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved aducanumab as the first

medication that specifically targets the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s disease.

A similar drug, lecanemab, was approved in January 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab

are human antibodies that target amyloid plaques and help their removal from the brain.

The use of these drugs to treat early-stage Alzheimer’s requires that doctors perform

diagnostic tests to detect amyloid in the brain, either through a special PET scan

or by testing cerebral spinal fluid. These diagnostic methods can be difficult for

some people to access. The closest location to Montana for an amyloid PET scan is

in Spokane, Washington. However, on the horizon are plasma biomarker tests which are

performed on blood samples. This is exciting and critical in rural states like Montana

because they will not only streamline diagnosis and treatment but will also aid in

bringing clinical trials to our state.

Aducanumab was approved by the FDA via an accelerated (versus a traditional) approval

process, resulting in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) only covering

the drug (and required testing) for people participating in FDA or National Institutes

of Health (NIH) approved clinical trials. Lecanemab was also initially approved under

an accelerated pathway, but as of July 6, 2023, has received traditional approval

from the FDA, which has opened doors for broad CMS coverage. A third antibody treatment,

donanemab, is also expected to receive traditional FDA approval in late 2024 and thus,

CMS coverage looks promising for this medication as well.

There remains a great need to broaden these recent advances in therapy to discover

even more effective Alzheimer’s treatments and prevention strategies. Fortunately,

the US government is dedicating resources to escalate research progress. In March

2022, the National Alzheimer’s Project Act was signed into law, which ensures annual

federal funding for Alzheimer’s disease research will be more than $3.5 billion. These

funds will help develop new therapies and move more than 143 therapies currently in

the clinical trial pipeline toward FDA approval. Many researchers are moving away

from amyloid-targeted therapies and are instead aimed at other potential Alzheimer’s

disease-causing pathways such as inflammation, neuroprotection, metabolism, and the

gut-brain axis.

Additionally, there has been progress in studying non-pharmaceutical interventions

and prevention strategies, such as exercise, for Alzheimer’s disease. In 2022, positive

results on reducing cognitive decline in older adults were reported with low-impact

exercise and with a daily multivitamin. These trials investigating lifestyle changes

may be more pragmatic and accessible in a rural setting, given the lack of specialty

providers and the distance often required to travel for specialized care in rural

states.

While there is no magic pill to ward off aging and cognitive decline, the future is

bright for Alzheimer’s disease research and treatments. There is a research program

in Montana offered by the McLaughlin Research Institute in Great Falls. Scientists

there are dedicated to helping ease the burden on Montana families by facilitating

clinical trials and researching new potential therapies and diagnostics.

They have launched the HERO Registry for a Healthier Montana: Help Expand Research

Opportunities. With this registry, they are seeking individuals who are willing to

take part in future clinical research studies. Any person of any age and health status

can register, as researchers need participants who have a neurodegenerative disease

(including Alzheimer’s disease) as well as healthy control participants. For more

information visit: mclaughlinresearch.org/hero.

Summary

Since Alzheimer’s first discovery in 1906, researchers have sought to identify the

cause and have tested various treatment options. While scientists around the world

continue to work on early diagnosis and treatment targets, local Montana scientists

are also working hard to ensure Montanans have access to the newest and best treatment

options for this degenerative brain disease.

References

Agricultural Occupations and Alzheimer’s: Potential Causes, Signs, and Early Diagnosis

- Arora, Kanika, Zu, Lili, Bhaginadh, Divya, et al. Dementia and Cognitive Decline in Older Adulthood: Are Agricultural Workers at Great

Risk? National Library of Medicine. Sept 2021. academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/76/8/1629/6066539

- Arora, Kanika. Press Release: Study shows working in agriculture poses higher risk of developing dementia. Great Plains Center for Agricultural Health. Jan 19, 2021. https://gpcah.public-health.uiowa.edu/press-release-study-shows-working-in-agriculture-poses-higher-risk-of-developing-dementia/

- Coelho, Fabio C, et al. Agricultural Use of Copper and Its Link to Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules. June 10, 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7356523/

- Gibson, Allison, and Anderson, Keith. Difficult diagnoses: Family caregivers’ experiences during and following the diagnostic

process for dementia. May 2011. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias 26(3) 212-217.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21362754/

- Gould, Andrew. Rural dementia: We need to talk. Jan 11, 2017. www.plymouth.ac.uk/news/rural-dementia-nil-we-need-to-talk

- Kienlen, Alexis. Living on the farm with Alzheimer’s. Oct 2014. www.agcanada.com/2014/10/living-on-the-farm-with-alzheimers

- Montana Alzheimer’s and Dementia State Plan: Addressing the Current and Future Needs of Individuals and Families with Alzheimer’s

Disease and Related Dementias. 2016. mtalzplan.org

- National Institute on Aging. How Is Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosed? www.nia.nih.gov/health/how-alzheimers-disease-diagnosed

- National Institute on Aging. How Biomarkers Help Diagnose Dementia. www.nia.nih.gov/health/how-biomarkers-help-diagnose-dementia

- Rasmusseen, Jill, and Langerman, Haya. Alzheimer’s Disease — Why We Need an Early Diagnosis. National Library of Medicine. Dec 2019.

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6935598/ - Ronnlund M, Sundstrom A, Adolfsson R, et al. Self-Reported Memory Failures: Associations with Future Dementia in a Population-Based

Study with Long-Term Follow-Up. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Sept 2015. 63(9):1766-73. agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jgs.13611

- Rural Health Information Hub. Health and Healthcare in Frontier Areas. www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/frontier

- Smyth, W., Fielding, E., Beattie, E. et al. A survey- based study of knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease among health care staff. BMC Geriatrics 13, 2 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-2

- Sturm, Emily Terese, et al. Risk Factors for Brain Health in Agricultural Work: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. March 2022. (19(6) 3373. www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/6/3373

Alzheimer’s and other Dementias: NOT a Normal Part of Aging

- Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org/about

- Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. 2023. Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Dementia-friendly Rural Communities Guide. 2019. www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-07/AS_DF_NEW_Rural_Guide_Online_09_07_19.pdf

- Jepsen, McGuire, Poland. Farming with Alzheimer’s Disease. 2013. Ohio State University. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/AEX-982.9

- Fifield, Kathleen. Dementia vs Alzheimer’s: Which is it? AARP. www.aarp.org/health/dementia/info-2018/difference-between-dementia-alzheimers.html

- Kienlen, Alexis. Living on the farm with Alzheimer’s. Oct 2014. www.agcanada.com/2014/10/living-on-the-farm-with-alzheimers

- National Center for Health Statistics. Mortality in the United States. 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm - National Center for Health Statistics. Mortality in the United States. 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/states/montana/mt.htm#lcod

- Rubin, Emma. Elderly population in US by state. Consumer Affairs. 2022. www.consumeraffairs.com/homeowners/elderly-population-by-state.html

Progression of Alzheimer's

- Graff-Radford, Johnathon, and Lunde, Angela M. Mayo Clinic on Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias. Mayo Clinic Press. 2020.

- Kienlen, Alexis. Living on the farm with Alzheimer’s. 2014. www.agcanada.com/2014/10/living-on-the-farm-with-alzheimers

- Living with Alzheimer’s in Rural Communities Can Be Challenging. 2021. www.alz.org/eastohio/news/living-with-alzheimers-in-rural-communities-can-be

- Alzheimer’s disease. Mayo Clinic. www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350447

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. alzheimers.gov

- Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias Education and Referral (ADEAR) Center. National

Institute on Aging. www.nia.nih.gov/health/about-adear-center

- National Care Planning Council. www.longtermcarelink.net/eldercare/nursing_homes.php

Alzheimer’s and Caregiver Wellness

- Be a Healthy Caregiver. Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/caregiver-health/be_a_healthy_caregiver

- Caregiver Stress. Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/caregiver-health/caregiver-stress

- Samuels, Claire. Caregiver Statistics: A Data Portrait of Family Caregiving in 2023. June 15, 2023. www.aplaceformom.com/senior-living-data/articles/caregiver-statistics

- Schmall, Vicki, Bowman, Sally, and Pratt, Clara. Helping Memory-Impaired Elders: A Guide for Caregivers. 2020. Oregon State University.

https://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog/pub/pnw-314-helping-memory-impaired-elders-guide-caregivers - Schmall, Vicki, Bowman, Sally, and Pratt, Clara. Coping with Caregiving: How to Manage Stress When Caring for the Elderly. 2020. Corvallis, OR. Oregon State University. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog/pub/pnw-315-coping-caregiving-how-manage-stress-when-caring-elderly

- Schmall, Vicki, Sturdevant, Marilynn, and Cleland, Marilyn. The Caregiver Helpbook: Powerful Tools for Caregivers. 2018, third edition. Portland, OR. Legacy Health System. https://store.extension.iastate.edu/product/The-Caregiver-Helpbook-Powerful-Tools-for-Caregivers

Communicating about an Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

- Aging Care, How to Tell Family That Mom or Dad has Alzheimer’s Disease. www.agingcare.com/articles/telling-family-about-elderly-parents-alzheimers-diagnosis-138156.htm

- Sharing Your Diagnosis. Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/help-support/i-have-alz/know-what-to-expect/sharing-your-diagnosis

- Helping Families and Friends. Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org/help-support/i-have-alz/live-well/helping-family-friends

- Telling people about your dementia diagnosis. Alzheimer’s Society. www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/daily-living/telling-people-about-your-dementia-diagnosis

- Helping Family and Friends Understand Alzheimer’s Disease. National Institute on Aging. www.nia.nih.gov/health/helping-family-and-friends-understand-alzheimers-disease

Hope for the Future: Treatments or a Cure for Alzheimer’s?

- Alzheimer’s Impact Movement. (n.d.). Investing in Alzheimer’s research. www.alzimpact.org/research

- Baker, L.D., Cotman, C.W., Thomas, R., Jin, S., Shadyab, A.H., Pa, J., Rissman, R.A.,

Brewer, J.B., Zhang, J., Jung, Y., LaCroix, A.Z., Messer, K. and Feldman, H.H. (2022),

Topline Results of EXERT: Can Exercise Slow Cognitive Decline in MCI? Alzheimer’s &

Dementia, 18: e069700. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.069700

- Baker LD, Manson JE, Rapp SR, Sesso HD, Gaussoin SA, Shumaker SA, and Espeland, MA.

(2023). Effects of cocoa extract and a multivitamin on cognitive function: A randomized clinical

trial. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 19(4), 1308-1319. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12767

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2023, Jan 6). Press release CMS statement on FDA accelerated approval of Lecanemab. CMS.gov.

www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-statement-fda-accelerated-approval-lecanemab - Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (2023, July 6). Press Release Statement: Broader Medicare Coverage of Leqembi Available Following

FDA Traditional Approval. CMS.gov. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/statement-broader-medicare-coverage-leqembi-available-following-fda-traditional-approval

- Cummings J, Lee G, Nahed P, Kambar MEZN, Zhong K, Fonseca J, Taghva K. (2022). Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2022. Alzheimer’s and Dementia-Translational

Research & Clinical Interventions, 8(1). e12295. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12295

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, July 8). How is Alzheimer’s disease treated? National Institute on Aging. www.nia.nih.gov/health/how-alzheimers-disease-treated

Copyright © 2024 MSU Extension

We encourage the use of this document for nonprofit educational purposes. This document

may be reprinted for nonprofit educational purposes if no endorsement of a commercial

product, service or company is stated or implied, and if appropriate credit is given

to the author and MSU Extension. To use these documents in electronic formats, permission

must be sought from the Extension Communications Director, 135 Culbertson Hall, Montana

State University, Bozeman, MT 59717; E-mail: publications@montana.edu.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Montana State University and Montana State